How Chowdeck plans to succeed where Jumia Food failed — Part 1

“Online food delivery is a cost-intensive business that is low-margin and scale driven.” — DoorDash COO Christopher Payne

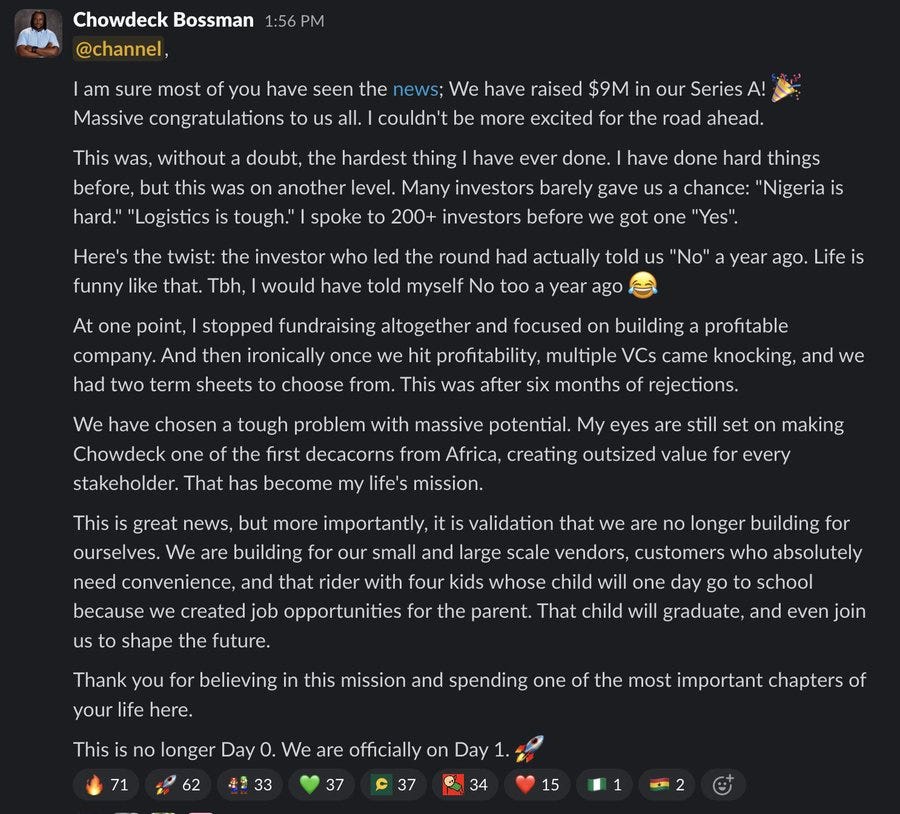

Nigerian food delivery platform Chowdeck announced its $9 million Series A on Monday — one of the largest fundraises for a local African food delivery player to date.

It’s a big deal in a globally challenging sector and the stakes are high.

In recent months, Jumia Food, Bolt Food, and others have exited Nigerian and African markets, citing “challenging economics” and operational difficulties.

Yet Chowdeck claims profitability, having scaled to 1.5 million customers and 20,000+ riders in 11 cities across Nigeria and Ghana.

That growth comes against a backdrop that should theoretically kill convenience spending: Consumer purchasing power has eroded drastically across Nigeria as the price of staple foods and essential items like petrol has skyrocketed.

Yet paradoxically, food delivery in Nigeria grew at a nearly 200% CAGR between 2021 and 2024, reaching ₦50-70 billion in GMV annually according to Paystack, the leading payment processor for companies in the space.

So how was Chowdeck able to ride that wave while Jumia Food drowned?

The autopsy of Jumia Food: Upside-down contribution margins

To understand Chowdeck, a good place to start is with an examination of Jumia Food's failure.

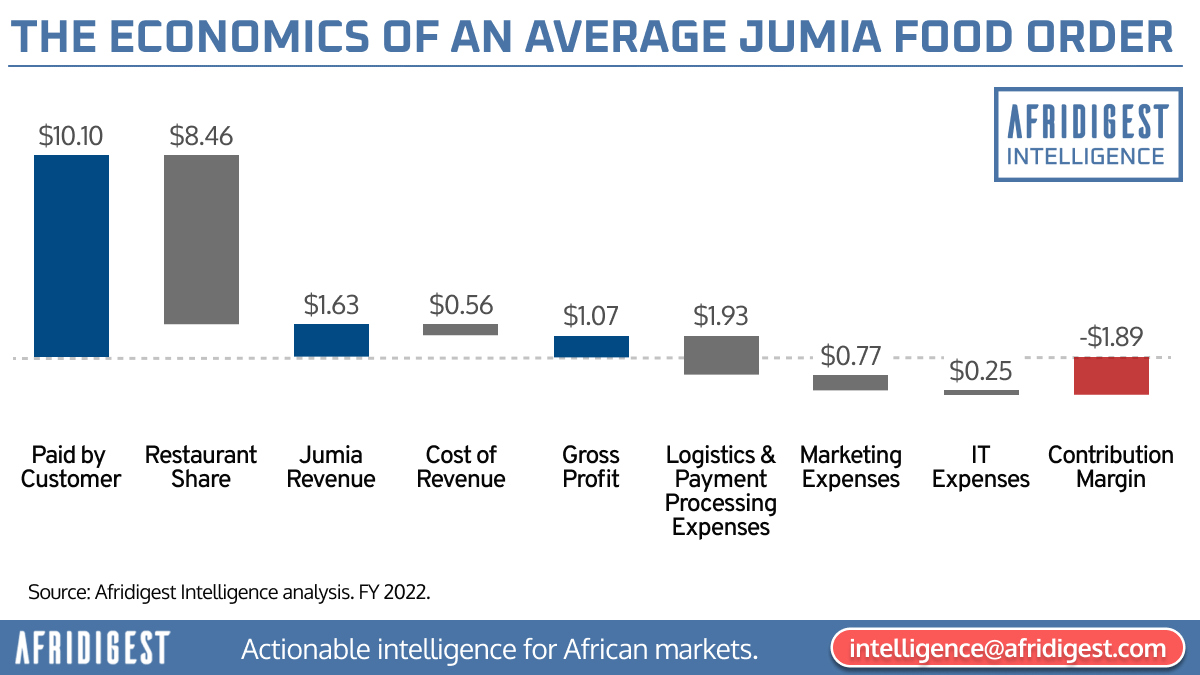

My analysis of Jumia’s financials last year revealed brutal unit economics for the company’s food delivery business:

The math was simple — and devastating:

Average customer payment: $10.10

Jumia’s revenue per order: $1.63 (16% take rate)

Fulfillment costs alone: $1.93

Net contribution margin: -$1.89 per order

Jumia Food lost money on every single order, with fulfillment costs exceeding total revenue. Even without accounting for marketing, technology, and overhead costs, the business was fundamentally broken.

Sure, the food delivery unit processed 11 million orders and $115 million in GMV in 2022, but every order deepened the parent company’s losses.

ICYMI: I spoke about Jumia and why the company killed Jumia Food on the BBC’s Focus on Africa podcast (12/22/2023) — the Jumia Food question comes at the 4:55 mark.

Why Jumia Food's fulfillment costs were so high

At a high level, certain structural factors likely drove Jumia Food’s fulfillment costs:

Infrastructure mismatch: Jumia’s logistics system was designed for e-commerce parcels, not on-demand food delivery. So the features that are ideal for food logistics — ultra-high-density delivery zones, short-haul routing, route clustering, sophisticated geotagging, demand forecasting, etc. — were underdeveloped or missing entirely, leading to inefficient resource allocation.

Internal dynamics: When standalone food delivery platform HelloFood rebranded to Jumia Food and came under the Jumia umbrella in 2016, it was seen as a customer acquisition engine for Jumia’s main e-commerce business and a driver of top-line sizzle rather than bottom-line steak. This perception drove misaligned incentives and allowed poor unit economics optimization to fester until the company’s founding CEOs were fired.

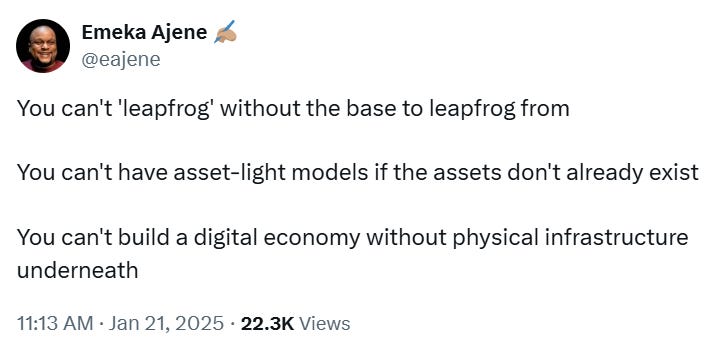

Poor market timing: Jumia Food launched in 2012 when Nigeria's digital payment infrastructure was nascent. They had to accept cash on delivery and spend heavily on user education — costs that Chowdeck and other platforms in the post-Jumia Food generation can avoid. (“The single most important factor in a startup’s success is timing.”)

Local context as a competitive advantage

Chowdeck’s founding team argues that something else was at play: Jumia and others with similar food delivery models were solving for the wrong market.

While Jumia Food focused largely on pizzas and burgers — foods Nigerians might order weekly or monthly — Chowdeck targeted what people actually eat daily.

“No one eats pizza every day. Nobody eats burgers every day,” Aluko explained on a recent podcast. “But delivering amala, delivering jollof rice — that’s different. That’s what people eat every day."

That insight drove Chowdeck to onboard local ‘bukkas’ — roadside restaurants selling traditional Nigerian food.

While it required significant technology customization — e.g., SMS-based order notifications for vendors without smartphones — it created sustainable, high-frequency demand.

The infrastructure advantage: Standing on the shoulders of giants

Chowdeck launched into a fundamentally different ecosystem than Jumia Food encountered in 2012.